In the past 30 years, tens of thousands of children have been freed from working in slave-like conditions in the clothing factories and carpet workshops of South Asia and the cocoa farms of Africa. Their freedom is the life’s work of Indian-born Kailash Satyarthi.

Hailing from Vidisha in Madhya Pradesh, the former electrical engineer and university lecturer founded Bachpan Bachao Andolan (the Save the Children Movement) in 1980 and, in the years since, he has fought for children’s rights in more than 144 countries.

In the 1980s, his group set up a certification system to guarantee that rugs were made without child labour. In 1999, his activism saw the International Labour Organization outlaw the worst forms of child labour, which include bonded labour and the trafficking of children to become workers. He has also actively rescued children from dangerous situations.

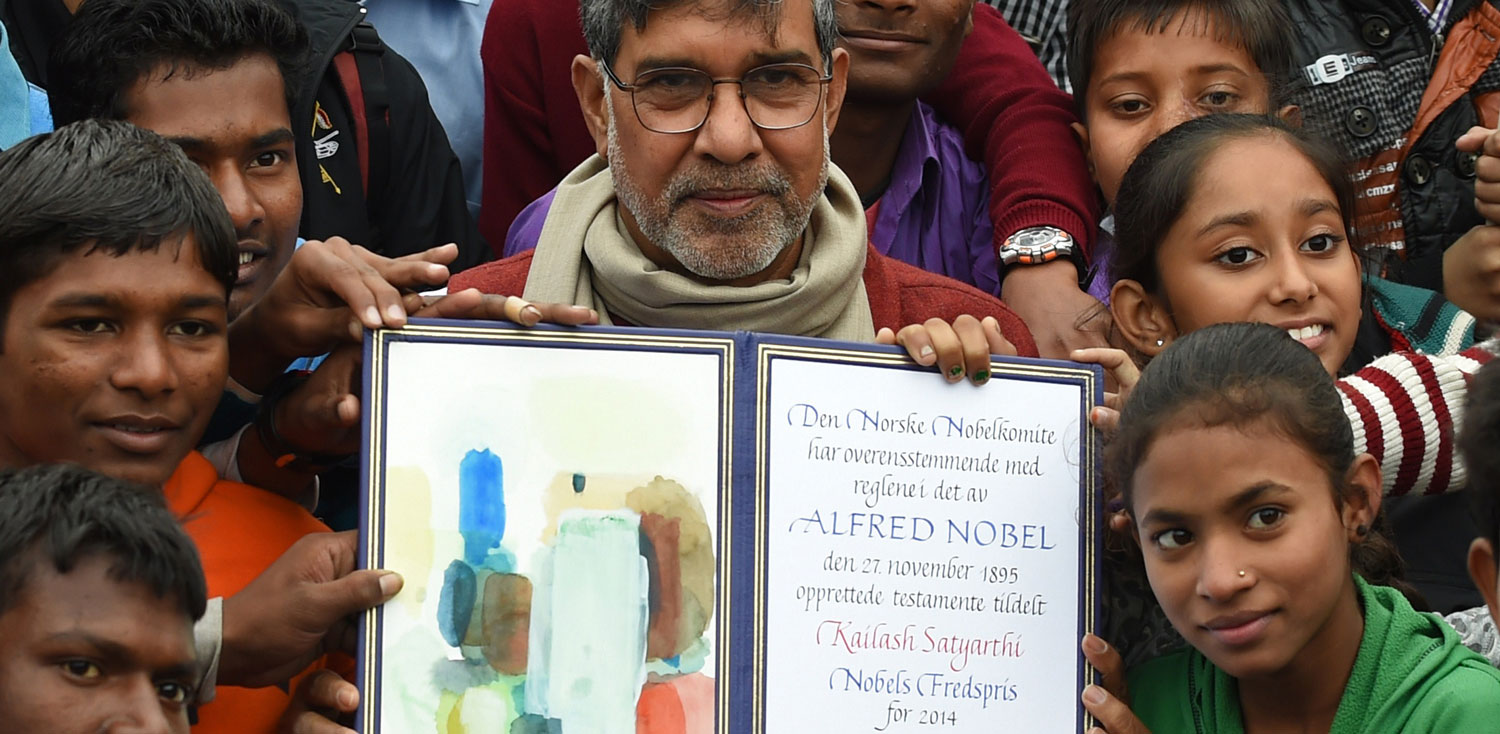

Satyarthi’s lifetime of work was formally recognised in 2014, when he won the Nobel Peace Prize along with Pakistani child activist Malala Yousafzai.

In his acceptance speech, Satyarthi declined the Nobel Committee’s request for a lecture, “because, I am representing here – the sound of silence, the cry of innocence and the face of invisibility. I represent millions of those children who are left behind and that’s why I have kept an empty chair here as a reminder. I have come here only to share the voices and dreams of our children – because they are all our children.”

AIM chief executive David Pich spoke to Satyarthi for AIM’s book, The 7 Skills of Very Successful Leaders (to be released next year by Major Street Publishing), and says: “Mr Satyarthi epitomises the very essence of http://leadershipmatters.com.au/new-in-leadership/2016/june/ethical-leadership-quotes/.”

DAVID PICH: What inspired you to stop being an engineer and work for the rights of children instead?

KAILASH SATYARTHI: The first spark came on my very first day of school when I encountered a boy sitting outside the school gate looking for a job. I was five-and-a-half and the boy was my age. That disturbed me, shocked me, and eventually made me angry. Everyone was trying to convince me it was common and these are poor children who have to work, but I was not convinced.

One day I gathered my courage and went straight to his father (a cobbler) and asked, “Sir, why don’t you send your son to school?” He told me that he had never thought about it; his grandparents and parents had been working since childhood and so was his son. Then he said: “Perhaps you don’t know it, but we people are born to work.”

For me it was complicated. I didn’t see why some people were “born to work” at the cost of their childhood, freedom, education, healthcare – I refused to accept that. I also refused to accept that some people are born to work for others at the cost of their freedom.

That spark slowly grew. After I graduated as an engineer and was teaching at university, the issue was so close to my heart I decided to follow my heart rather than my mind.

Most people called me crazy because it was at a time when child labour and child slavery were not issues addressed in India or elsewhere in the world. So it was difficult, but I started with a magazine dedicated to the children who were the most vulnerable and neglected, as well as women and other sections of society, to help create an awareness about this issue and then finally we started freeing children.

“Economic growth alone results in disparities, imbalance and inequalities, which are always the source of tensions and violence. We have to think of other aspects of human development, other than just economics.”

DP: You’ve been attacked by employers on some of the rescues you’ve done. Can you give us a situation that you’ve been in that has been dangerous to you?

KS: Oh it has happened several times but I will give you one example. Once some mothers came all the way from Nepal to rescue their daughters who were trafficked away to work in the circus industry in India. So we started doing some research and found where they were working, but we knew it would be difficult because the owner was a powerful person – a criminal.

We were taken inside. Circuses are like small fortresses and I got the feeling the girls may have been taken away, which was why they were letting us in. The police and magistrates were with us, and the circus owner put this gun to my head. A policeman warned this guy that there was a camera running, then he jumped at the cameraman.

My colleagues, my son, the mothers and I decided to leave the place immediately. But this guy was so angry he ordered his colleagues to kill us. We were all badly injured. My driver had fled with fear but finally a journalist helped us – he put us in his car and took us to hospital and somehow we were saved.

But I decided not to give up – these daughters are my daughters. I believe in Gandhian tradition [the method of non-violence and passive resistance used by Mahatma Gandhi], so I decided to go on a hunger fast, because I did not believe in retaliating in any other manner. I sat in front of the state assembly in the capital and fasted for six days. This created tremendous awareness of this issue in India and all across the world. People were expressing solidarity about this issue. There was anger and protest against this [circus] mafia. Finally the High Court of this state took up this issue and ordered the chief of police to retrieve the girls.

So far 24 girls were rescued – we were only looking for 12 in the first place.

But we did not leave it there because my fight was not against the employer, though he tried to kill me – my fight was against this evil. So I decided to knock on the door of the Supreme Court of India to appeal that this was more or less slavery and that the employment of children in the circus industry should be outlawed. We won, finally. Five or so years later the Supreme Court changed the law.

DP: You’ve called for a total ban on child labour under age 14 and a ban on hazardous child labour under the age of 18. How far is humanity away from seeing that realised?

KS: Before 1999 there was no law against child slavery, child trafficking and the use of children in hazardous occupations. That was the reason we had that crazy idea to organise the Global March against Child Labour. Then the whole world woke to this serious problem.

The core demand was that there should be a serious law to combat the worst demands of child slavery immediately and with a sense of urgency. The result was a new International Labour Organization convention on the worst forms of child labour. It was agreed that no child would be allowed to work in hazardous occupations if they are under 18 and no child under 14 shall be allowed to work in developing countries (age 15 in industrialised countries).

Five countries have not ratified the conventions and unfortunately India is one of the five. The Indian government has brought some amendments to the law [regarding family businesses] which I do not agree with.

AIM chair Ann Messenger and chief executive David Pich met with Kailash Satyarthi in Delhi this year.

DP: One of the things you have said is “economic growth and human development need to go hand in hand”. But many leaders believe economic growth is everything. What can a leader do to get those things right?

KS: Economic growth has been the main focus in many countries. For instance, in the United States well-educated young people become so frustrated and violent that they take guns from their fathers’ wardrobes and kill people. If economic growth alone sufficed, why is this happening? Similarly in India, we see young people competing to push each other aside because opportunities are limited – they are not the most satisfied people.

Economic growth alone results in disparities, imbalance and inequalities, which are always the source of tensions and violence. So we have to think of other aspects of human development, other than just economics.

DP: How did you raise awareness of the issue of child labour with consumers?

KS: When I launched this carpet consumer campaign [GoodWeave] back in the mid to late 1980s, there was no awareness about the issue of child labour, but I had a big faith in consumers – who are usually parents or grandparents. I wanted to connect with the inbuilt compassion in these consumers. I believed that if they know these things are made by child slaves they won’t buy them. We have seen enormous success in South Asia. The number of children in the carpet industry has declined over the last 20 years from 1 million to 200,000 now.

Once people are conscious of the issue, their consciousness would not remain only with the carpet industry. They will start demanding child labour-free chocolate, shoes and other products. And it is happening now. People are getting more aware and conscious.

Most importantly, people should realise if they are buying products made from the exploitation, misery and pain of children it is not good for society or for anyone. Better quality goods can always be produced by adults who are skilled workers.

DP: Do you think the responsibility lies with consumers or should companies be leading the way, especially big global companies?

KS: Consumers may not know if the goods they are buying are free from child labour but they need to keep asking for that guarantee. In India, for example, we visited schools in an attempt to have children boycott the firecrackers made by children in South India. Millions of children across the country started demanding to celebrate birthdays and festivals such as the Festival of Light – Diwali – with candles, not the firecrackers made by children. It was so successful that the entire firecracker industry had to change its behaviour and practices. They also started a certification scheme making sure that the adult workers are working in safe conditions.

But I think it works both ways. The consumers are the bottom-up approach – they should keep on demanding those things. It definitely has a ripple effect.

In the US and in Europe, I visited carpet shops with activists and asked for child labour-free carpets. When they couldn’t assure us they had these, we refused to buy. In front of us, they starting ringing and asking the same of their suppliers. So the consumer’s power is definitely supreme in the free market economy, but simultaneously it’s also necessary that we should hold the leaders of these big brands to account.

“Leaders should have a deep conviction in what they believe. It could be right or wrong, history will determine that, but they should have the courage to jump into the ring instead of waiting for someone else to go first.”

DP: Who does this? Governments?

KS: Of course governments have a responsibility, but most governments promote free markets so they try to limit the local laws. Consumers, the media, the civil society organisations and the human rights bodies play an important role by exposing the problem of child labour in certain industries.

I’m sure that no company can flourish at the expense of the blood and sweat of children, and allowing child labour to continue does not actually bring much economic benefit to them. The benefit goes to the middlemen – the suppliers at different levels.

DP: I would say this is an issue of leadership and it’s about taking a stand about things that are absolutely not right. Have you got examples of where this has worked with the organisations or industries you have talked to, where they’ve made an ethical decision to do the right thing?

KS: In the early days in my discussions with the carpet industry, I was only able to convince two exporters who made a moral decision and took a strong ethical stance that they didn’t want to benefit from the labour of children. That was in 1991, and then they were able to fetch the support of another six, so then there were eight. Then I launched a separate organisation for those who did not deal in child labour.

There was a similar situation with the chocolate industry in the Ivory Coast and Ghana. When the company leaders come forward with some courage on these issues, they will never lose out. I’m not talking about being a martyr or a hero; if everyone in the business sector took this leadership role, they benefit economically – in fact they have huge gains out of it.

More importantly, their board members, officers, shareholders and workers feel satisfied a different type of production culture has been created. Everybody feels engaged and happy because they are doing the right thing.

DP: It’s not just about looking at profit and turnover, the numbers side of things – you are looking at the impact of your processes. I think more organisations are seeing that these things have to be balanced.

KS: You can see the changes over time. Earlier on, businesses were quite happy with donating money to charity, then they became involved in a more substantial and sustainable sort of philanthropy. Now we are in a third stage of corporate social responsibility, where due diligence is done on the supply chain and so on. Some governments and countries have gone further, to “corporate social accountability”, where there is transparency in the supply chain.

DP: It takes leadership to see that transparency is better for business.

KS: More corporate leaders have to shift a little from conventional leadership to a compassionate leadership, which is moral and ethical. I know every business is for profit, and I am not against that, but if you are able to bring an element of compassion to the businesses, that will make them more sustainable. It gives a different kind of satisfaction and pleasure; it creates a different kind of working and leadership environment.

DP: So what are the leadership traits that you admire in other people?

KS: Creativity, courage and conviction. Such leaders should have a deep conviction in what they believe. It could be right or wrong, history will determine that, but they should have the courage to jump into the ring instead of waiting for someone else to go first.